I am going to bet that not many people have heard of the “Overton Window”. There can be many reasons for this. One is that it is a relatively new concept. Another may be that is usually used in conjunction with the prevailing political debate. Finally, it was generated in a “Think Tank” type environment and those types of terms do not usually migrate out into the greater population. Be that as it may, I think it is a very interesting term in that to me it is just as applicable to business (and probably many more environments that I have not considered) as it appears to be to politics.

First, a little history and definition as to what the Overton Window is and how I came about looking into it.

I first came across the term “Overton Window” while reading one of the plethora of political analyses purporting to explain what is currently occurring in American politics. It discussed how various individuals were responsible for shifting what was, and what wasn’t politically acceptable to discuss. As I wish to discuss business and not politics I won’t name any of the individuals but suffice it to say there are not as many people as you might think that are capable of or are shifting what is acceptable in the current political discourse. The majority of them are usually just credited with screaming about one thing or another, depending on which side of any given issue they happen to reside.

So, since the Overton Window was mentioned, and I didn’t know what it was, so I then went and searched the term on the web. The following is the simplest description that I could come up with:

“The Overton window is the range of ideas tolerated in public discourse, also known as the window of discourse. The term refers to Joseph P. Overton, who claimed that an idea’s political viability depends mainly on whether it falls within the window, rather than on politicians’ individual preferences. According to Overton’s description, his window includes a range of policies considered politically acceptable in the current climate of public opinion, which a politician can recommend without being considered too extreme to gain or keep public office.”

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Overton_window

So, basically the Overton Window is the range of ideas that are “acceptable” to talk about at any given time. That doesn’t mean that they are the correct ideas. It only means that they are politically correct, or ideas that can be talked about without significant fear of a negative response.

We have all seen examples of what the possibly best solution to any specific problem may be, only to find out that the prevailing political climate renders this solution politically unacceptable. It also notes that this window can shift depending on a variety of factors. Ideas that may be in the window at one time, or for one administration, may not be in it at another time or for another administration.

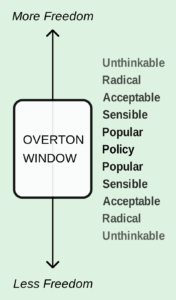

“Overton described a spectrum from “more free” to “less free” with regard to government intervention, oriented vertically on an axis, to avoid comparison with the left-right political spectrum. As the spectrum moves or expands, an idea at a given location may become more or less politically acceptable. Political commentator Joshua Treviño postulated that the degrees of acceptance of public ideas are roughly:

• Unthinkable

• Radical

• Acceptable

• Sensible

• Popular

• Policy

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Overton_window

The Overton Window (with Trevino’s degrees of acceptance) is usually depicted as follows:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Overton_window

As I have noted before, reading about something like this always gets me to thinking, which as I have also noted before can be a dangerous thing for me to do. It got me to thinking about why so many organizations talk so incessantly about the need for change, but then react with an immune system like resistance response to those proposals that can in fact generate real change.

It got me to thinking that the Overton Window is a limiting factor in that according to its precepts, only those changes that fall within the relatively modest window can or will be acceptable. True or significant change would probably place that policy outside of the Overton Window, which would mean that it is politically unacceptable for consideration.

This would explain why only minor or incremental types of changes seem to find their way into the corporate (or political) application. Too great a change, regardless of its potential necessity or benefit would find itself outside the range of acceptable change for the then business (or political) administration.

The only way to compensate for the smaller than necessary amplitude of change is to increase the frequency of change. I think that the idea of many, smaller changes being more acceptable than fewer, larger changes is what has given rise to the now industry standard vernacular of business such as:

“The rate of change is not going to slow down anytime soon. If anything, competition in most industries will probably speed up even more in the next few decades.” – John Kotter

http://www.ideachampions.com/weblogs/archives/2011/04/1_it_is_not_the.shtml

On the other hand, and probably a little less known or accepted we have:

“If you want to make enemies, try to change something.”

– Woodrow Wilson https://toprightpartners.com/insights/20-transformational-quotes-on-change-management/

I’ll let you guess who’s proposed changes were within the Overton Window and whose changes were probably outside of it.

I think what Overton recognized about politics is probably reasonably applicable to business as well. All organizations have a political aspect to them. This is the personal and interpersonal side of things. Stakeholders have committed to a then acceptable and approved course of action. Significant change or movement away from that direction could cause a perceived loss face or position.

So, how can this change limiting window be moved or enlarged?

In politics, the answer is relatively simple: Elect someone else. If those in office refuse to accept that a new direction is needed because of whatever commitments and ties they have to the current direction (or whichever special interest group), replace them with someone new who’s views more closely align with the new direction or change that is desired.

Okay, so what do you do in business to expand an organization’s ability to change, since you can’t readily elect new business leaders?

Therein lies the issue. Organizations are not elected. They are put in place from the top down. CEO’s are selected in a closed environment by Boards of Directors. The CEO’s then surround themselves with executives that will support and enable their programs. This type of directional change then cascades in one form or another throughout the organization. On the other end of the organizational spectrum, managers likewise look for team members who will also support and enable their objectives and assignments.

With this sort of top-down approach to organizational structures it would appear that in order to affect a desired or needed change of any significant magnitude, you would have to make a change at least one to two levels above the desired change location in order to affect the Overton Window that is limiting the desired change. Normally, as a matter of course, changes of this type, or at this level do not occur easily in a business organization, unless the entire system, and its performance are under a great deal of stress, and by then, many times it is too late.

I think the concept of the Overton Window does a very good job of explaining why organizations talk so much about the need for change but seem significantly limited as to the size, type and amount of change that they can actually affect. As long as the existent organizational team and structure remain in place, change of any real magnitude will be very difficult when the topics and paths lie outside the window of acceptable discourse for the existing team.

While it may be desirable and sought after that change be made from “the bottom up”, this type of change can only really occur when the bottom of the structure, or in the political sense, the voter makes the change by electing someone else, and the management structure (those elected) listens to and responds to the mandate. In a business organization the mandate comes down from the executives, not up from the employees.

Change in any environment is difficult. I think the concept of the Overton Window goes a long way toward explaining why so many organizations say they want to or need to change but fail to make any significant or meaningful changes. It is usually not until the situation reaches a point where it becomes incumbent to replace specific organizational or business leaders with others, who may have a different window as to what is now the new and acceptable discourse on what and how to change.