Time cards have been a symbol of manufacturing productive efficiency for years. I think we have all seen images of production and manufacturing associates dutifully standing in line to “punch in” at their appointed shift on the time clock. It seemed to be a marvelous mechanism to maintain, measure and direct those resources associated with production, in the most efficient manner. It is where the phrase “on the clock” originated. You came in and they started paying you when you “clocked in” and they stopped paying you when you “clocked out”. It was efficient.

By the way, the “Time Clock” that has become so universal when talking about clocking in and clocking out, first made its appearance on the business scene in the late nineteenth century.

” An early and influential time clock, sometimes described as the first, was invented on November 20, 1888, by Willard Le Grand Bundy, a jeweler in Auburn, New York. His patent of 1890 speaks of mechanical time recorders for workers in terms that suggest that earlier recorders already existed, but Bundy’s had various improvements; for example, each worker had his own key. A year later his brother, Harlow Bundy, organized the Bundy Manufacturing Company, and began mass-producing time clocks.” https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Time_clock

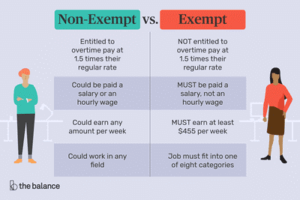

There then arose the dichotomy in business where there were those that were “paid by the hour” (those on the clock), or waged employees, and those that were paid a set amount per period of time, or salaried employees. Waged employees were referred to as Non-Exempt and Salaried employees were referred to as Exempt. These definitions were laid down in 1938 by the Fair Labor Standards Act. https://www.investopedia.com/terms/e/exempt-employee.asp

Below is a brief comparison of the differences between the two:

So, why am I talking about one hundred and thirty year old inventions (Time Clocks) and eighty year old employee definitions (Fair Labor Standards Act)?

The reason is pretty simple. As the production and standardization processes that have been used in manufacturing have found their ways into the other disciplines and aspects of business, so has the cost tracking and charging of those resources responsible for doing the manufacturing.

We are now asking our exempt employees to fill out time cards associated with the work they are doing. This in and of itself is probably not a bad thing, however it engenders a new and different behavior in the exempt employee. It is this new “Time Card” behavior in exempt employees that can a detrimental effect on the business.

For lack of a better definition, exempt employees are paid by the “job” as opposed to by the “hour”. If an exempt employee must work late hours and weekends to complete their assignment, they do not get paid any more. They do however get the satisfaction of knowing the completed their task, regardless of how long it took them.

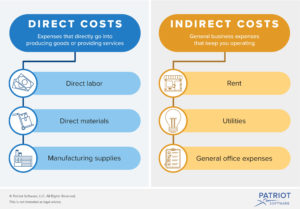

The idea of having exempt / salaried employees track their time, was to better associate costs directly with specific projects or activities. This association gave rise to the exempt employees who could directly associate their activities with specific items or revenue producing functions, and those that could not associate their work with specific items. Those that could be directly associated with specific products, projects and functions were called “Direct” labor, and those that could not be directly associated were called “Indirect” labor.

“The essential difference between direct costs and indirect costs is that only direct costs can be traced to specific cost objects. A cost object is something for which a cost is compiled, such as a product, service, customer, project, or activity. These costs are usually only classified as direct or indirect costs if they are for production activities, not for administrative activities (which are considered period costs).

The concept is critical when determining the cost of a specific product or activity, since direct costs are always used to compile the cost of something, while indirect costs may not be assigned to such a cost analysis. It can be too difficult to derive a cost-effective methodology for the assignment of indirect costs; the result is that many of these costs are considered part of corporate overhead or production overhead, which will exist even if a specific product is not created or an activity does not occur.” https://www.accountingtools.com/articles/the-difference-between-direct-costs-and-indirect-costs.html

The following as a good way to think about this. I promise I will get to my point about Time Cards and why this is important soon.

So, all of this work associated with slicing and dicing the time that salaried employees spend on their various activities is being done to understand what portion of their work can be directly associated with a cost object (Direct) and what portion cannot (Indirect). Why is this important anyway? It’s pretty simple.

All businesses want to reduce, minimize and otherwise exit overhead or indirect costs from the business equation.

Every business has the objective of reducing indirect costs, otherwise known as “Overhead”. As noted, these are the costs that cannot be directly associated with revenue production.

So, when Exempt, salaried employees are asked to fill out time cards, and they have multiple options, both “Direct” and “Indirect” to associate their time with, which are they going to choose? Knowing the corporate desire to minimize, reduce and exit Indirect and overhead costs from the business, they will naturally migrate their time charging to “Direct” functions and charges.

On the surface this might seem like a wonderful way for companies to reduce overhead, and in some instances, it will work. However, if you have the financial responsibility for one of these cost objects, you will want to be able to closely monitor the number of people and the amount they can charge to your cost object. This monitoring, or policing activity and capability again creates an incremental overhead.

It is essentially a transference of the overhead responsibility from the labor pool owner (of salaried, exempt employees), to the Cost Object owner.

Labor pool owners are always going to try and minimize the amount of their labor that is not directly associated with a revenue producing cost object. They will want to show the preponderance of their time, as reported by time cards, as being directly associated with a revenue producing function. Engineering groups, development groups, support groups and just about every other group will begin to display this behavior once time cards are utilized in this fashion.

The fear for them is that if they show too much time spent on overhead functions, they will be subject to a cost reduction activity in an effort to reduce overhead.

The results of this “Time Card” behavior are manifold:

- With the pressure to be associated with, and charge to only Direct costs, the direct costs associated with specific cost objects can become inflated by excessive charging. Since direct costs are “above the line” in accounting and margin terms, this could result in inflated and non-competitive prices.

- There will now be a somewhat adversarial relationship in place between those groups wanting to charge directly to cost objects, and those groups that are responsible for maintaining those cost object budgets, and the corporate inefficiencies and friction that this creates. There is also the non-productive time that will be spent challenging, changing and rectifying those charges as they come in.

- There is non-productive time, effort and cost for increasingly capable corporate tools to maintain, monitor and control this type of charging effort. How do you control who should and should not charge to a cost object?

Time cards, like process can be a good thing. But like process, they should not be viewed as a replacement for judgement. When you move costs associated with time cards from indirect labor to direct labor, it may solve a corporate desire to reduce perceived overhead and indirect labor expenses, but it also creates several new issues and expenses associated with monitoring and controlling those charges. Due to how costs are accounted for in direct versus overhead items, it can also change both the cost profiles, margins and ultimately pricing profiles in the market.

Time cards in the salaried or exempt employee environment can and will change behaviors. Labor resource groups will increase their focus on having cost objects to charge to as opposed to understanding that there is to be expected a certain amount of slack time that they will have. Instead of the labor resource pool manager managing this slack level, time cards in essence transfer this issue to the cost object owners to try and control and manage.

Time cards for salaried and exempt employees can provide a better level of visibility into how time is spent and what employees are working on. It does however carry with it what is known as “The Observer Effect”.

I always try to sneak a little physics into any discussion.

“Observer effect (physics) In physics, the observer effect is the theory that simply observing a situation or phenomenon necessarily changes that phenomenon. This is often the result of instruments that, by necessity, alter the state of what they measure in some manner.” https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Observer_effect_(physics)

As long as business is aware of how behaviors are changed, and what may need to be done to compensate for these changes, there can be value in them. However, without those considerations they can create an entire new set of issues for a business to deal with, and may result in little to no efficiency gains.