For just about as long I can remember I have heard that what you have learned, and what you know, and your experience are valuable. They are the tools of your trade in the knowledge-based businesses and economies. And to some extent I think this idea may still apply, at least in part. I think that there will always be a need and desire for intelligent people in the businesses of today and in the future. One of the best accepted ways to demonstrate intelligence is through the attainment of a college degree. This may or may not actually demonstrate the intelligence level, but it is the now somewhat de-facto threshold for employment in the technology and knowledge-based economy. However, I think that now more than ever before, where you live is going to be one of the key driving factors to your employability.

This is particularly the case for the larger companies and organizations. I am sure that there are those that are reading this and are thinking: “What is he talking about? The rise of virtual offices, and working at home, and so on and so forth, have removed location from the context of the employment equation.” (That employment equation being the value that you generate for the company needs to be perceived as greater than the fully loaded cost of your employment by the company.) Please bear with me, as I think you may be thinking too small, as the true effects of globalization start to take effect in areas other than factory production.

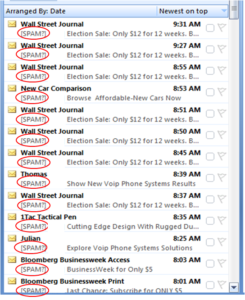

As usual, there was a genesis for this direction of thought. It came in the form of an article by Erin Fuchs, Deputy Managing Editor at Yahoo Finance, titled “Why Wages Aren’t Rising Faster”. (https://www.yahoo.com/finance/news/why-wages-arent-rising-faster-192629608.html). In the article he examines why, in a period of historically low unemployment, what amounts to the usual economic model of high demand for labor versus a stable supply has not resulted in higher wages, as the model would predict.

He points out three things that are occurring that are holding wages down. The first element he points out is that the data now indicates that there is no longer a growth in employee productivity occurring. I don’t know if this is due the virtualization of the office and the accompanying loss of “synergy”, or if the process driven structure of organizations is starting to reach an asymptotic limit. What it does mean is that growth now will be linearly linked to the number of people doing the same type of work. Sort of like that factory production line model, and I think we all know what eventually happened to the factory production line job. I’ll come back to this idea in a minute.

The second element was the “…misleading nature of average wage growth figures…”. I take this as a direct reference to Mark Twain, who is credited with saying: “There are three kinds of lies: lies, damned lies, and statistics.” Simply put, this means that one Bill Gates retiring from the workforce can and will offset many of the lower paid positions’ wage gains that might for example affect the food service industry. This is also an interesting topic that I’ll revisit.

The third piece to the wage stagnation puzzle was the ability for companies to opt to hire overseas, in lower-cost countries, instead of paying the higher wages being demanded in the higher-cost countries.

This seems to me to be the element that ties the previous two items together.

If you are working at home, in a higher cost country, why can’t someone else do the same work at home in a lower cost country. As we noted earlier, we have removed the distance issue from the virtual organization. So, while it may not have mattered where in the country you lived in performing your job, it now seems to matter to a much larger level, what country you live in when performing your job.

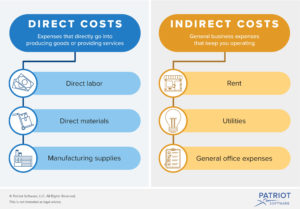

When the employee productivity curve starts to flatten out, as it appears to be doing, the only way to continue to show business improvement is to reduce the cost of each of the linearly added employees. Processes that have more and more finely defined employee functions can now be applied to less costly employees in lower cost countries. Any quality or productivity issues can be absorbed in the overall value of the resulting total cost reduction.

I think we are already seeing the start of this approach to business. Those disciplines that do not require direct customer or market interfaces are already moving out of the expensive higher-cost countries. Production and manufacturing were the first to go. Research and Development were not too far behind. Don’t confuse the spark of creativity with the work associated with developing a product from it. Soon Human Resources, Finance and Accounting followed. These were also essentially well defined, repeatable functions with well-defined processes and procedures.

This essentially left Sales (a direct customer interfacing function), marketing (a culturally dependent function) and operations (the customer delivery function) as the only mandatory functions that need to remain in a high cost country (or any country for that matter). Any other corporate function, or support function could and would be moved as soon as it made economic sense to the organization.

In the past it was argued that when the average wage rates increased, it was the more highly educated that benefited as opposed to those in the lower paid roles and positions. It now seems that the fruits of this type of environment have also sown the seeds of the issue that is now faced. It is now the higher cost, well-educated roles that are being lost to lower-cost countries, while the lower waged roles are now benefiting from the new laws aimed at increasing the minimum wage.

The interesting dichotomy here is that while the government may be imposing a new, elevated floor to the wage pool in the form of an increased minimum wage, businesses are in the process of imposing a de-facto ceiling or upper limit on what wages they are willing to pay in the same market. So, while the minimum wage may be rising in the strong employment market, the group that had benefited the most from strong labor markets, the educated and experienced, are now losing ground.

This has created an interesting situation and some even more interesting trends. Highly educated, highly experienced, and highly paid people are being shed by larger organizations as the company looks to continue to show bottom line growth. This availability of talent is seeing their market opportunity change. They can bring their benefits to smaller organizations, but at usually smaller wages as that specific type of labor supply increases. This is indeed what has been seen in many instances.

Or they can move more toward the “Gig Economy” where there seems to be growth in what could best be described as “Fractional” employment. Fractional employment is a situation where a smaller company may need an experienced, knowledgeable employee, but just does not need them full time, or all the time. So instead of offering a lower paying full-time position, they can offer a higher paying (based on hourly rates) part time role. This then leaves the contracted employee with the opportunity to either fill the rest of their available time with other similar roles, or not, as they choose.

This enables both the employee to maintain their desired income level, but only through employment at multiple locations, and allows companies to reduce their resource employment costs by no longer having to employ expensive resources full-time, when they are desired, but not effectively needed.

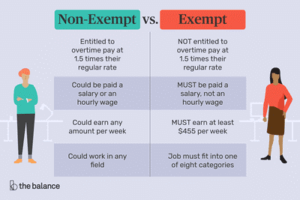

The interesting addition here is that the “benefits” usually associated with employment (insurance, vacation, etc.) are reduced for both the employer and the employee. Remember, employee benefits cost employers more than thirty percent of total employee expenses and are not usually paid to contracted or part-time employees. (https://smallbusiness.chron.com/cost-employee-benefits-employer-2694.html)

This brings us to the reckoning. The trend has started in high cost countries and markets. Higher cost higher educated positions in the larger organizations for the most part have started moving to lower cost countries and markets in increasing numbers. It would seem that nothing short governmental intervention in this sort of labor migration will be able to stop it. These types of employment regulations may or may not exist to greater levels outside of North America, but again it would seem that they will only be effective in slowing down this evolution, not stopping it.

This change cannot but help to start to reduce the wage levels that were here to fore thought of as the higher-level incomes. There will be more, higher educated and experienced resources chasing fewer onshore opportunities. Even though employment levels may be high, the higher end, higher paying opportunities once thought of as only available to the highly educated will start to become less available.

One way to combat this outflow of positions is to reduce the cost of onshore employment. The movement to fractional employment should continue to gain traction. The reduction in the pay rates for these “highly paid” positions should also start to flatten out and even come down. Finally, as we have seen the end of pensions and retirement compensation in the last few decades, we should also expect to see a reduction in the benefits such as insurance, vacation, etc., (and the accompanying corporate expense) that companies offer.

So, while wages may be going up for some of the labor market, it would appear that they are heading down for those at the upper end of the labor market, even in such a strong employment market. Employment may indeed be at historical highs, but those that were once thought to benefit the most from these types of market conditions are now poised to face both reduced roles and reduced opportunities as businesses continue to try to reduce their labor costs.